[ad_1]

Context:

The CoWin portal came under criticism due to the absence of a privacy policy.

In February 2021, the minister of state for health informed the Lok Sabha that CoWin follows the privacy policy of the National Digital Health Mission (NDHM), which is the Health Data Management Policy.

Other digital health initiatives, such as telemedicine, hospital management systems and insurance claims management, are also tied to this Policy.

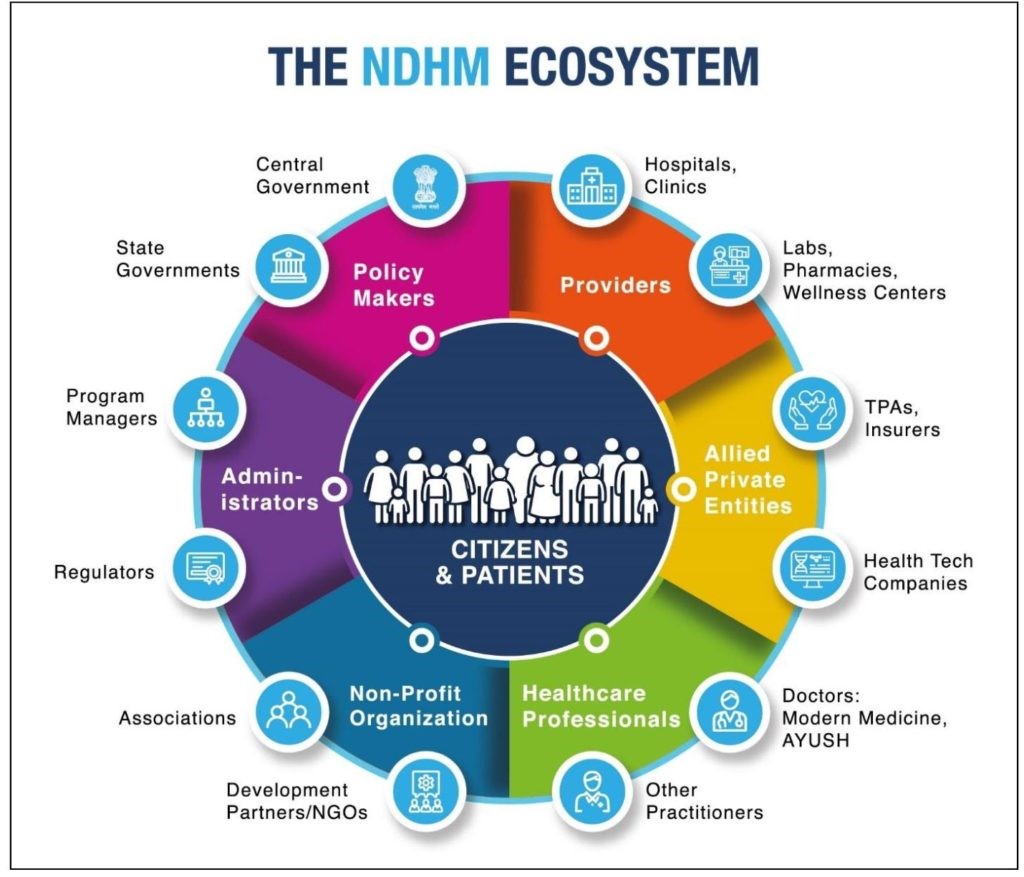

National Health Authority (NHA) is the apex agency of the Government of India responsible for the design, roll- out, implementation and management of Ayushman Bharat and the National Digital Health Mission (NDHM) across the country.

It is no exaggeration to say that the Policy forms the backbone of the NDHM.

Health Data Management Policy:

- The National Health Authority (NHA) has released the Health Data Management Policy of the National Digital Health Mission (NDHM) in the public domain for comments and feedback.

- The Policy seeks to develop a national health information system, by facilitating the creation of Unique Health Identification (UHID) for individuals and healthcare providers; and the collection, storage, processing and sharing of personal health information, as electronic health records (EHRs).

- Every individual’s UHID is linked to his or her EHR. While digitisation enables seamless and efficient exchange of information, it also entails significant risks to privacy, confidentiality and security of personal health data.

- The Policy purports to mitigate these risks, through two guiding principles: “security and privacy by design” and individual autonomy over personal health data.

- However, fundamental design flaws may end up increasing instances of personal health data breaches.

- The Policy rightly sets out privacy by design and individual autonomy as its guiding principles. However, vague provisions and on-ground implementation are failing to adhere to these principles.

Therefore, Contrary to the Right to Informational Privacy:

- The Supreme Court, in Puttaswamy, held that the right to informational privacy is a fundamental right and any encroachment on this must be supported by law, also calling for enacting a comprehensive data protection legislation.

- Contrary to this, the digitisation process being rolled out under the Policy is not supported by any law.

- This remains a concern as unauthorised disclosures and breaches would cause serious and irreparable harm to individuals.

- The Policy itself establishes the NDHM, which will function like a regulator performing legislative, executive and quasi-judicial functions.

- Setting up a regulatory authority entails a law that defines the boundaries within which it can function, while ensuring independence from government interference and accountability to Parliament.

- Instead, the Policy leaves it entirely to the NDHM, an executive authority, to define its own governance structure.

Problem of weak accountability extends to personal health data:

- Recently, the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India warned insurers against using leaked personal health records of COVID-19 patients to deny coverage or block claims.

- The problem of weak accountability extends to personal health data as well.

- For example, the Policy does not require reporting of personal data breaches to affected individuals.

- This not only impedes the rights to information and access to grievance redress, but also increases the possibility of illegitimate state surveillance.

- For instance, a recent RTI query revealed that the chief medical officer of the Kulgam district in Jammu and Kashmir was surreptitiously sharing Aarogya Setu users’ data with local police authorities.

- The privacy by design framework may be bogged down by weak accountability mechanisms vis-à-vis secondary use of digital health data for research and policy planning, particularly by private firms.

- The Policy permits sharing of aggregate and anonymised health data, on the premise that anonymisation conceals individuals’ identity.

- However, several studies have shown that anonymised datasets can be easily de-anonymised to link back to personally identifiable information, risking individual privacy.

Risking individual privacy and identifiable information:

- The Policy also does not limit the use of aggregate health data to public health purposes, and prohibit data monetisation.

- Without strict purpose limitation, private firms may use people’s health data to enhance profits, at the cost of individual rights and societal interests.

- For example, insurance companies may freely use granular health data to profile and score individuals, leading to denial of coverage for high-risk groups and volatility in premium amounts.

- The other guiding principle of individual autonomy is invoked through ‘informed consent’ for collecting and processing personal health data.

- However, the proposed consent framework is so constricted that individuals may ultimately end up with little or no control over their data.

- For one, the Policy mandates informed consent only prior to the collection of data, in case of any change in the privacy policy or in relation to any new or unidentified purpose.

- This suggests that one-time consent for one or more broad purposes may be sufficient, as opposed to informed consent for every instance of personal data processing.

Therefore, need for a Public Health Surveillance System:

- In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) in partnership with the Government of India launched the Integrated Health Information Platform (IHIP) within the IDSP program.

- The IHIP is a digital web-based open platform that captures individualized data in almost real-time, generates weekly and monthly reports of epidemic outbreaks and early warning signs and captures response by ‘rapid response teams’, for 33+ disease conditions.

- Predicting/Forecasting and Preparedness for Epidemic Outbreaks for communicable and emerging epidemics of non-communicable disease, such as MDR-TB, NIPAH outbreak etc.

- Guiding Prevention and Health Promotion Strategies: Identify new/hidden reservoirs and sources of infection, block chains of rapid transmission and limit the resulting morbidity, disability or death.

- Responding to Outbreaks and Guiding Future Programs of Disease control: Surveillance can help create standard protocols to interpret actionable medical data in real time and subsequently use tools like genetic mapping to target variations or susceptible hosts.

NITI Aayog introduced: The National Health Stack:

The National Health Stack will facilitate collection of comprehensive healthcare data across the country.

Designed to leverage India Stack, subsequent data analysis on NHS will not only allow policy makers to experiment with policies, detect fraud in health insurance, measure outcomes and move towards smart policy making, it will also engage market players (NGOs, researchers, watchdog organizations) to innovate and build relevant services on top of the platform and fill the gaps.

Way forward:

The design is geared to generate vast amounts of data resulting in some of the largest health databases with secured aggregated data that will put India at the forefront of medical research in the world.

With the adoption of the technology approach, the government’s

policies on health and health protection can achieve:

- Continuum of care as the Stack supports information flow across primary,

secondary and tertiary healthcare - Shift focus from Illness to Wellness to drive down future cost of health

protection - Cashless care to ensure financial protection to the poor

- Timely payments on Scientific package rates to service providers, a strong

lever to participate in government-funded healthcare programs - Robust Fraud detection to prevent funds leakage

- Improved policy Making through access to timely reporting on utilization

and measurement of impact across health initiatives and - Enhanced trust and accountability through non-repudiable transaction

audit trails.

Conclusion:

In a recent working paper, published by the Internet Freedom Foundation and the Centre for Health Equity, Law and Policy, examining of various implications arising from the Policy.

In a country with an uncertain cybersecurity environment, poor digital literacy and weak state capacity, the adverse implications can be particularly severe and widespread.

While addressing the gaps in the Policy is necessary, it is not sufficient.

A comprehensive data protection law (with health sector specific rules) as well as meaningful and sustained stakeholder engagement, are imperative for guiding the development of a digital health ecosystem in an effective, efficient and equitable manner.

[ad_2]