[ad_1]

Context:

Towards this, NITI Aayog recently published a road map document entitled “Health Insurance for India’s Missing Middle”.

However, to say the least, the report confounds all hopes and expectations of a credible pathway to universal health coverage (UHC) for India.

The report brings out the gaps in the health insurance coverage across the Indian population and offers solutions to address the situation.

- Low Government expenditure on health has constrained the capacity and quality of healthcare services in the public sector.

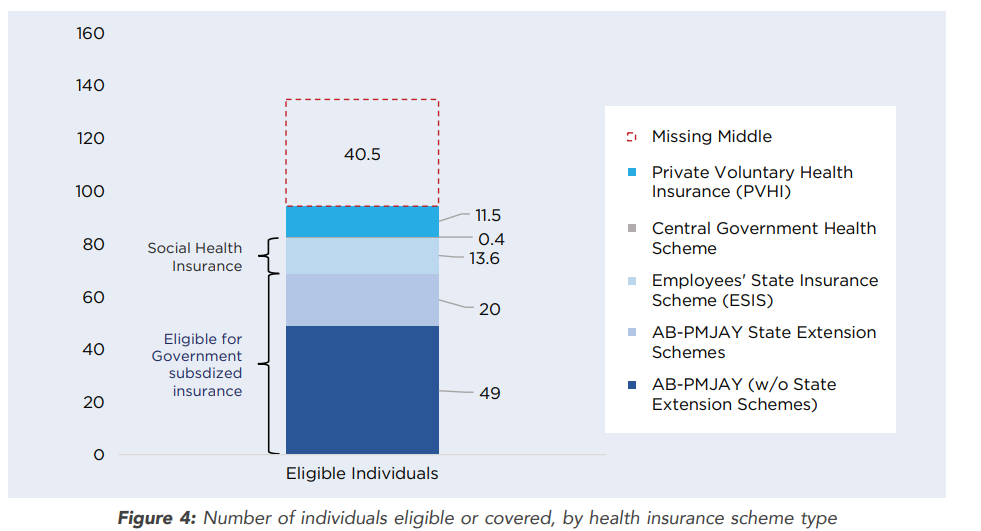

- At least 30% of the population, or 40 crore individuals – called the missing middle in this report – are devoid of any financial protection for health.

- In the absence of a low-cost health insurance product, the missing middle remains uncovered despite the ability to pay nominal premiums.

- Covering the left out segment of the population, commonly termed the ‘missing middle’ sandwiched between the poor and the affluent, has been discussed by the Government recently.

“Health Insurance for India’s Missing Middle” report:

The report proposes voluntary, contributory health insurance dispensed mainly by private commercial health insurers as the prime instrument for extending health insurance to the ‘missing middle’.

Government subsidies, if any at all, will be reserved for the very poor within the ‘missing middle’ and only at a later stage of development of voluntary contributory insurance.

This is a major swerve from the vision espoused by the high-level expert group on UHC a decade ago, which was sceptical about such a health insurance model as the instrument of UHC and advocated a largely tax-financed health system albeit with private sector participation.

Out-patient care needs to be addressed:

- An even more untenable case has been made with respect to out-patient department (OPD) care insurance coverage, which includes doctor consultations, diagnostics, medicines, etc.

- The report rightly acknowledges that OPD expenses comprise the largest share of out-of-pocket expenditure on health care, and concomitantly have a greater role in impoverishment of families due to health-care expenses.

- The report proposes an OPD insurance with an insured sum of ₹5,000 per family per annum, and again uses average per capita OPD spending to justify the ability to pay.

- However, the OPD insurance is envisaged on a subscription basis, which means that insured families would need to pay nearly the entire insured sum in advance to obtain the benefits. This is the last thing one would equate with UHC.

- Clearly, this route is unlikely to result in any significant reduction of out-of-pocket expenditure on OPD care, which beats the whole purpose of providing insurance.

- Any cost savings or benefits that accrue would be due to using low-powered physician payment modes and a more integrated and coordinated pathway of care.

- However, their contribution is likely to be nominal and at least be partly offset by the administrative costs involved in insurance.

- Individuals are likely to be largely indifferent to such an OPD insurance scheme, particularly if it restricts choice of health-care providers.

Health Insurance for India’s Missing Middle: Recommendations:

Report has recommended three models for increasing the health insurance coverage in the country.

- The first model focuses on increasing consumer awareness of health insurance.

- The second model is about “developing a modified, standardized health insurance product” like ‘Arogya Sanjeevani’, a standardised health insurance product launched by the Insurance Regulatory Development Authority of India (IRDAI) in April 2020.

- A “slightly modified version” of the standardised Aarogya Sanjeevani insurance product will help increase the update amongst the missing middle.

- The third model expands government subsidized health insurance through the PMJAY scheme to a wider set of beneficiaries.

- This model can be utilized for segments of the missing middle which remain uncovered, due to limited ability to pay for the voluntary contributory models outlined above.

- This is the only model out of three proposed which has fiscal implications for the Government.

- Though this model assures coverage of the poorer segments on the missing middle population, premature expansion of PMJAY can overburden the scheme.

- The report is more about expanding the footprints and penetration of the private health insurance sector.

- Further, the report looks to attain the elusive UHC with few or no fiscal implications for the Government, which is an absurd idea by any stretch of the imagination. Such a disposition is highly dismaying in the aftermath of COVID-19.

In-patient care also needs government support:

- Those with even a rudimentary understanding of health policy would know that no country has ever achieved UHC by relying predominantly on private sources of financing health care.

- Evidence shows that in developing countries such as India, with a gargantuan informal sector, contributory health insurance is not the best way forward and can be replete with problems.

- But even when we look at international precedents of contributory social health insurance models, some very important traits stand out, for example, significant levels of government subsidy to schemes; not-for-profit mode of operation; and some important guarantees for health.

- The NITI report sweepingly ignores these fundamental precepts.

- For hospitalisation insurance, the report proposes a model similar to the Arogya Sanjeevani scheme, albeit with lower projected premiums of around ₹4,000-₹6,000 per family per annum (for a sum insured of ₹5 lakh for a family of five).

- There would be a standard benefit package for all, and the insured sum will be between ₹5,00,000 and ₹10,00,000.

- Insurance will be dispensed largely by commercial insurers who would compete among themselves.

Conclusion:

The report has also suggested sharing of the government scheme data with the private insurance companies.

Government databases such as National Food Security Act (NFSA), Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana, or the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) for agricultural households can be shared with private insurers after taking consent from these households, suggesting an outreach strategy.

The National Health Policy 2017 envisaged increasing public health spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2025. Let us not contradict ourselves so early and at this crucial juncture of an unprecedented pandemic.

[ad_2]