[ad_1]

Context:

Over the past week, a big part of the focus on the IMF has been due to the controversy surrounding its Managing Director’s role in the alleged rigging of the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Rankings while she was the chief executive at the Bank.

But, away from the controversies, the IMF has also been in the news for unveiling its second World Economic Outlook (WEO).

To be sure, twice every year, April and October, the IMF comes out with its WEO.

The WEO reports are significant because they are based on a wide set of assumptions about a whole host of parameters such as the international price of crude oil and set the benchmark for all economies to compare and contrast.

On the whole, the IMF’s central message was that the global economic recovery momentum had weakened a tad, thanks largely to the pandemic-induced supply disruptions across the planet.

IMF’s second World Economic Outlook (WEO) in 2021:

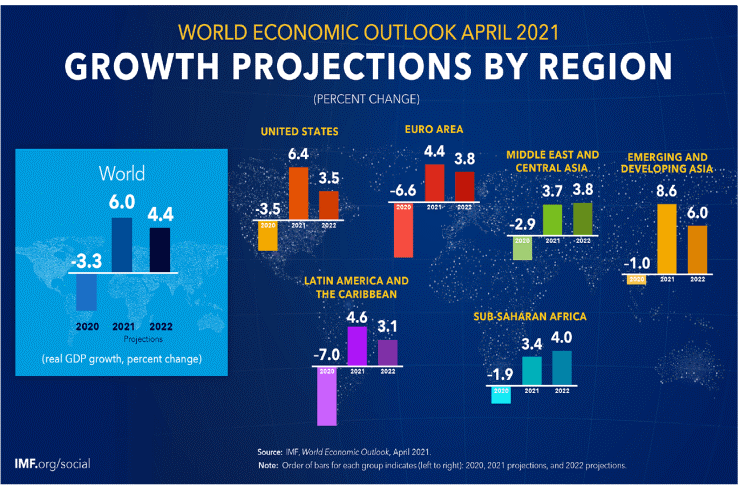

- Compared to July forecast, the global growth projection for 2021 has been revised down marginally to 5.9 per cent and is unchanged for 2022 at 4.9 per cent.

- This modest headline revision, however, masks large downgrades for some countries.

- The outlook for the low-income developing country group has darkened considerably due to worsening pandemic dynamics.

- But more than just the marginal headline numbers for global growth, it is increasing inequality among nations that the IMF was most concerned about.

- The dangerous divergence in economic prospects across countries remains a major concern.

- Aggregate output for the advanced economy group is expected to regain its pre-pandemic trend path in 2022 and exceed it by 0.9 per cent in 2024.

- By contrast, aggregate output for the emerging market and developing economy group (excluding China) is expected to remain 5.5 per cent below the pre-pandemic forecast in 2024, resulting in a larger setback to improvements in their living standards.

Two key reasons for the economic divergences:

One, Large disparities in vaccine access and,

Two, the difference in policy support (or the help provided by the respective governments).

While almost 60 per cent of the population in advanced economies are fully vaccinated and some are now receiving booster shots, about 96 per cent of the population in low-income countries remain vaccinated.

Emerging and developing economies, faced with tighter financing conditions and a greater risk of de-anchoring inflation expectations, are withdrawing policy support more quickly despite larger shortfalls in output.

IMF recent statements in unveiling of World Economic Outlook (WEO):

Employment around the world remains below its pre-pandemic levels, reflecting a mix of negative output gaps, worker fears of on-the-job infection in contact-intensive occupations, childcare constraints, labour demand changes as automation picks up in some sectors, replacement income through furlough schemes or unemployment benefits helping to cushion income losses, and frictions in job searches and matching.

Within this overall theme, what is particularly worrisome is that this gap between recovery in output and employment is likely to be larger in emerging markets and developing economies than in advanced economies.

Further, young and low-skilled workers are likely to be worse off than prime-age and high-skilled workers, respectively.

On the whole, India’s growth rate hasn’t been tweaked for the worse. In fact, beyond the IMF, there are several high-frequency indicators that have suggested that India’s economic recovery is gaining ground.

What about employment?

- The informal worker is defined as “a worker with no written contract, paid leave, health benefits or social security”.

- The organised sector refers to firms that are registered. Typically, it is expected that organised sector firms will provide formal employment.

- It is clear that the bulk of India’s employment is both in the unorganised sector and is of an informal nature.

- What this data shows is that if the informal/unorganised sector recovers at a slower pace than the formal sector, then the recovery in employment (relative to the recovery in output) will be even slower in India.

How big is India’s informal economy? How many people does it employ?

- In a 2019 paper, titled “Measuring Informal Economy in India”, National Statistical Office estimated the extent of India’ informal economy.

- The terms unorganised/ informal sector is used interchangeably in the Indian context.

- The informal sector/unorganised sector consists of enterprises which are own account enterprises and operated by own account workers or unorganised enterprises employing hired workers. They are essentially proprietary and partnership enterprises.

- The share of informal/unorganised sector GVA to the total is more than 50%. (Source: Computed from National Accounts Statistics, 2019)

- Of course, there are sectors such as Agriculture and allied industries where almost all the sector’s GVA is produced by those working in the informal sector.

- Then there are sectors such as Manufacturing where less than 23 per cent of the total GVA comes from the informal sector.

That was the contribution of the informal sector in total output.

Preparing for the post-pandemic economy:

Finally, it is important to deal with the challenges of the post-pandemic economy: reversing the pandemic-induced setback to human capital accumulation, facilitating new growth opportunities related to green technology and digitalization, reducing inequality, and ensuring sustainable public finances.

Recent developments have made it abundantly clear that we are all in this together and the pandemic is not over anywhere until it is over everywhere.

If Covid-19 were to have a prolonged impact into the medium term, it could reduce global GDP by a cumulative $5.3 trillion over the next five years relative to our current projection. It does not have to be this way.

The global community must step up efforts to ensure equitable vaccine access for every country, overcome vaccine hesitancy where there is adequate supply, and secure better economic prospects for all.

Conclusion:

In the context of what the IMF said about recovery in unemployment lagging output recovery, it matters to understand why we may not know about the unemployment distress in a large part of India.

That’s because, as it is often said, 90% of India’s jobs are in the so-called informal sector. More often than not, data on this part of the economy is quite patchy and inadequate.

The global economic recovery is continuing, even as the pandemic resurges.

The fault lines opened up by COVID-19 are looking more persistent near-term divergences are expected to leave lasting imprints on medium-term performance.

Vaccine access and early policy support are the principal drivers of the gaps.

[ad_2]