[ad_1]

Introduction:

Close to 700 million people worldwide live along the coast and there continue to be plans to expand coastal cities.

Therefore, understanding the risks involved from climate change and sea level rise in the 21st and 22nd centuries is crucial.

Sea level rise will continue after emissions no longer increase, because oceans respond slowly to warming.

The centennial-scale irreversibility of sea level rise has implications for the future even under the low emissions scenarios.

Sea level rise occurs mainly due to the expansion of warm ocean waters, melting of glaciers on land, and the melting of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. Global mean sea level (GMSL) rose by 0.2m between 1901 and 2018.

The average rate of sea level rise was 1.3 mm/year (1901-1971) and rose to 3.7 mm/year (2006-2018).

While sea level rise in the last century was mainly due to thermal expansion, glacier and ice sheet melt are now big contributors.

Context:

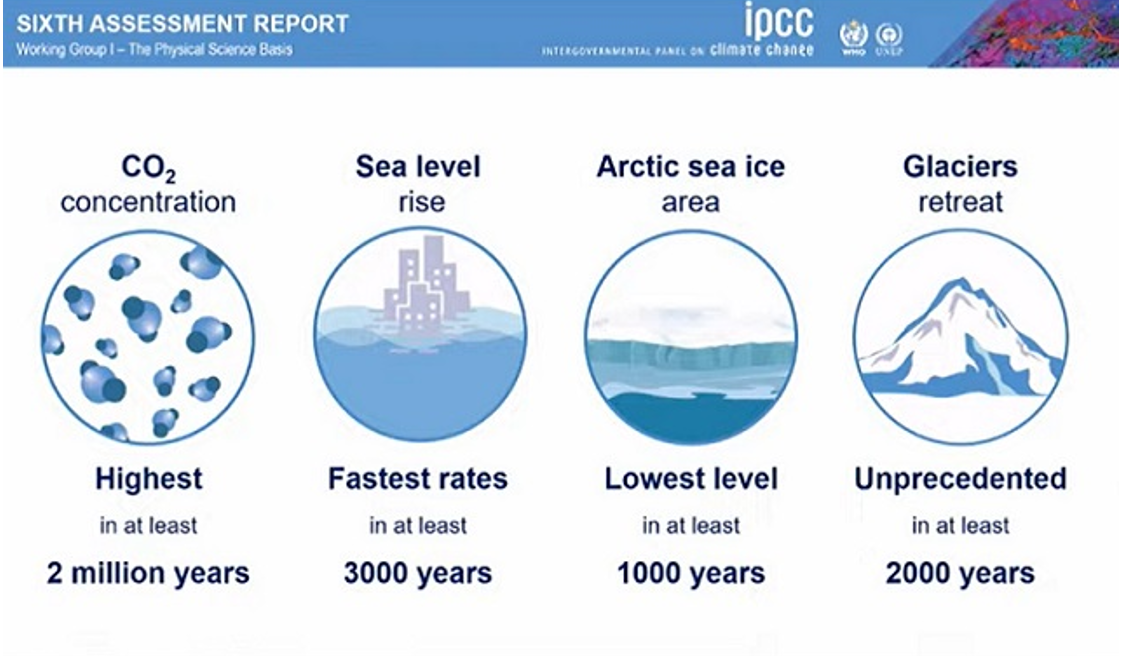

The recently published Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Report from Working Group I, ‘Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis’, is a clarion call for climate action.

It provides one of the most expansive scientific reviews on the science and impacts of climate change.

Scientists rely on ice sheet models to estimate future glacier melt. While these models have improved over the years, there are shortcomings in the knowledge and representation of the physical processes.

Assessment Report: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis:

The average global temperature is already 1.09°C higher than pre-industrial levels and CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is currently 410 ppm compared to 285 ppm in 1850.

Over 200 experts working in several domains of climate have put the report together by assessing the evidence and the uncertainties.

They express their level of confidence (a qualitative measure of the validity of the findings) ranging from very low to very high.

They also assess likelihood (a quantitative measure of uncertainty in a finding) which is expressed probabilistically based on observations or modelling results.

The report discusses five different shared socio-economic pathways for the future with varying levels of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The scenarios illustrated are the following:

- Very low and low GHG emissions, where emissions decline to net zero around or after the middle of the century, beyond which emissions are net negative;

- Intermediate GHG emissions;

- High and very high emissions where they are double the current levels by 2100 and 2050, respectively.

Even in the intermediate scenario, it is extremely likely that average warming will exceed 2°C near mid-century.

Extreme weather and its consequences:

Rising temperatures will reduce people’s physical ability to work, with much of South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Central and South America losing up to 250 working days a year by 2100.

- An additional 1.7 billion people will be exposed to severe heat and an additional 420 million people subjected to extreme heatwaves if the planet warms by two degrees Celsius compared to 1.5 degrees—the range laid out in the Paris Agreement.

- By 2080, hundreds of millions of city dwellers in sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia could face more than 30 days of deadly heat each year.

- Flooding on average will likely displace 2.7 million people annually in Africa. Without emissions cuts, more than 85 million people could be forced to leave their homes in sub-Saharan Africa due to climate induced impacts by 2050.

- A plus 1.5-degrees-Celsius world would see two or three times more people affected by floods in Colombia, Brazil and Argentina, four times more in Ecuador and Uruguay, and a five-fold jump in Peru.

- Some 170 million people are expected to be hit by extreme drought this century if warming reaches three degrees Celsius.

- The number of people in Europe at high risk of mortality will triple with three degrees Celsius warming compared to 1.5 degrees of warming.

Disease and other impacts:

- As rising temperatures expand the habitat of mosquitoes, by 2050 half the world’s population is predicted to be at risk of vector-borne diseases such as dengue fever, yellow fever and Zika virus.

- Without significant reductions in carbon pollution, an additional 2.25 billion people could be put at risk of dengue fever across Asia, Europe and Africa.

- The number of people forced from their homes in Asia is projected to increase six-fold between 2020 and 2050.

- By mid-century, between 31 and 143 million could be internally displaced due to water shortages, agricultural stresses, and sea level rise in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America.

Vulnerability in India:

- Communities along the coast in India are vulnerable to sea level rise and storms, which will become more intense and frequent.

- They will be accompanied by storm surges, heavy rain and flooding.

- Even the 0.1m to 0.2m rise expected along India in the next few decades can cause frequent coastal flooding.

- A speculator might think that if less than a metre sea level rise by 2100 is the likely scenario, they have another 60-80 years to continue developing infrastructure along the coast. That would not, however, be the right way to interpret the IPCC data.

- The uncertainty regarding a metre or more of sea level rise before 2100 is related to a lack of knowledge and inability to run models with the accuracy needed.

- Low confidence does not mean higher sea level rise findings are not to be trusted.

- In this case, the low confidence is from unknowns — poor data and difficulty representing these processes well in models. Ignoring the unknowns can prove dangerous.

- According to the UN Environment Programme Emissions Gap Report, the world is heading for a temperature rise above 3°C this century, which is double the Paris Agreement aspiration. And there is deep uncertainty in sea level projections for warming above 3°C.

Conclusion:

Adaptation to sea level rise must include a range of measures, along with coastal regulation, which should be stricter, not laxer, as it has become with each update of the Coastal Regulation Zone.

The government should not insure or bail out speculators, coastal communities should be alerted in advance and protected during severe weather events, natural and other barriers should be considered in a limited manner to protect certain vulnerable areas, and retreat should be part of the adaptation strategies for some very low-lying areas.

[ad_2]