[ad_1]

Introduction:

The provisional estimates of annual national income (2020-21), released on May 31 by the National Statistical Office, did not have any surprises, but for one, that is, there is nothing encouraging in the numbers.

India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contracted 7.3% in 2020-21, as per provisional National Income estimates released by the National Statistical Office, marginally better than the 8% contraction in the economy projected earlier.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contracted reasons:

The contraction in trade (-18.2%), construction (-8.6%), mining (-8.5%) and manufacturing (-7.2%) is a matter of concern as these sectors account for the bulk of low-skilled jobs.

The magnitude of contraction in the economy and the policy responses towards it raises an important issue, that is, the question of growth prospects for the next year.

The agriculture sector continued its impressive growth performance, reiterating that it still remains as the vital sector of the economy, especially at times of crisis.

The manufacturing sector continued its subdued growth performance, failing to emerge as the growth driver, with production interruptions due to localised lockdowns to be blamed.

Rising unemployment rate:

- Contextualising the current growth rates in terms of some other macroeconomic data would provide us a better perspective on growth recovery.

- The unemployment data released by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) which says, In May 2021, India’s labour participation rate at 40 per cent was the same as it was in April 2021.

- The unemployment rate shot up to 11.9 per cent from 8 per cent in April.

- A stable labour participation rate combined with a higher unemployment rate implies a loss of jobs and a fall in the employment rate.

- According to CMIE, over 15 million jobs were lost in May 2021, higher than the 12.3 million in November 2016, the month of demonetisation. May 2021 was also the fourth consecutive month of a fall in employment.

- The more worrying fact is that the cumulative fall in employment since January 2021 is 25.3 million of which 22.7 million were in the first quarter of FY 2021-2022, that is, during April and May.

- This shows that the second wave of the pandemic has already dented economic activities, postponing recovery further.

- The job losses also bring out the high informality and vulnerability of labour in India as of the total jobs lost during April-May, 17.2 million were of daily wage earners.

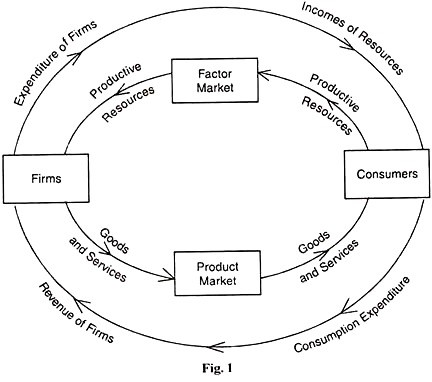

- We also know that aggregate demand and output growth have a positive correlation.

- Hence, the prospects of growth revival in the next year look bleak at the moment and from this perspective, it is worrying that in just April and May 2021, India lost 25 million non-farm jobs.

Low business confidence:

- Business confidence index (BCI), from the survey by the industry body FICCI, plummeted to 51.5 from 74.2 in the previous round.

- The survey also highlights the weak demand conditions in the economy. It says, “With household income being severely impacted and past savings being already drawn on during the first wave of infections, demand conditions can be expected to remain weak for longer.”

- Compounding this is the uncertainty arising out of the imposition of localised curbs due to the second wave of infections and a muddled vaccine policy in the country.

- Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) also throws some light on the shape of things to come.

- PMI has slipped to a 10-month low indicating that the manufacturing sector is showing signs of strain with growth projections being revised lower.

- Both BCI and PMI slipping down indicates that the overall optimism towards 2021-22 is low, which could impact investments and cause further job losses.

Demand recovery must be done for Growth recovery:

- Growth recovery depends on demand recovery. External demand looks robust as India’s exports touched $32 billion in May 2021, 67% higher than in May 2020 and 8% more than in May 2019.

- The combined increase in exports of April and May 2021 is over 12% indicating that global demand rebound is much faster than the domestic demand.

- Stimulus programmes and a sharp decline in COVID-19 infections seem to be aiding these economies. What needs to be addressed immediately is the crisis of low domestic demand.

- Since last year, the policy responses have been to rely on credit easing, focusing more on supply side measures, with more and more guarantees by the government to improve flow of credit to important sectors.

- There has been less direct action by the government to support the vulnerable to alleviate their hardships.

- There were some sector-specific measures to alleviate distress in certain sectors, which were timely.

However, some sector specific policy stance is unlikely to prop up growth for three reasons:

- First, the bulk of the policy measures, including the most recent, are supply side measures and not on the demand side.

- In times of financial anxiety, what is needed is direct state spending for a quick demand boost.

- Second, large parts of all the stimulus packages announced till now would work only in the medium term.

- These include policies related to the external sector, infrastructure and manufacturing sector.

- In fact, some of the policies towards agriculture, such as productivity enhancement through the introduction of new varieties, will only work over years.

- Third, the use of credit backstops as the main plank of policy has limits compared to any direct measure on the demand side as this could result in poor growth performance if private investments do not pick up.

- Further, the credit easing approach would take a longer time to multiply incomes as lending involves a lender’s discretion and borrower’s obligation.

- Interestingly, a tight-fisted fiscal policy approach comes at a time when conventional fiscal stimulus packages might not be enough as supply side issues arising out of episodic lockdowns need to be addressed simultaneously.

Public spending is the key:

- Right now, raising public spending is the only game in town left to the policymaker serious about bringing on a recovery.

- If we are to have it, though, we should accept a higher than budgeted deficit.

- The objective is to revive the economy, public spending is the instrument and the funding must be found. It need not involve money creation.

- India’s public debt is low by comparison with the OECD countries, and debt financing remains an option.

- Even if money financing is adopted, it need not cause accelerating inflation as some predict. Experience in India suggests otherwise.

- However, studies do show that any economic expansion would be inflationary if the production of food does not respond adequately.

- How the expansion is financed is less relevant for inflation at least in the near term. In any serious attempt at economic recovery, the focus must be on the food supply and not the money supply.

Conclusion:

The private corporate sector estimates of industries are based on other indicators like IIP, GST, etc. This may have implications on subsequent revision of these estimates

What is required now is a sharp revival in overall demand. Focusing on short-term magnified growth rates resting on low bases might be erroneous, as income levels matter more than growth rates at this juncture.

Focusing on growth rates has its merits in the long term as achieving higher income levels require sustained growth for longer periods.

[ad_2]