[ad_1]

Context:

In recent, the Environment Ministry published draft regulations on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), set to come into effect by the end of this year.

Disregarding the commitments made by the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016; the Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016; and the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), these regulations denote a backslide, particularly with respect to integration of the informal sector.

According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), India generates close to 26,000 tonnes of plastic a day and over 10,000 tonnes a day of plastic waste remains uncollected.

Draft regulations on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR):

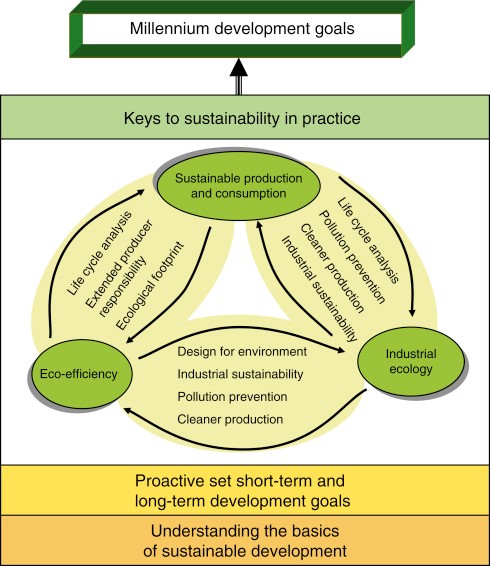

- EPR requires the manufacturer of a product, or the party that introduces the product into the community, to take responsibility for its life cycle.

- An FMCG company should not only account for the costs of making, packing and distributing a packet of chips, but also for the collection and recycling/reuse of the packet.

- In India, producers have externalised these costs due to the presence of a robust informal sector composed of waste pickers.

- By failing to mention waste pickers or outlining mechanisms for their incorporation under EPR, the guidelines are retrogressive.

- The SBM Plastic Waste Book attributes India’s high recycling rate to the informal sector.

- But the guidelines not only disregard waste pickers and don’t involve them as stakeholders in formulating the guidelines, but also direct producers to set up a private, parallel plastic waste collection and recycling chain.

The Draft guidelines fall short in three areas: people, plastics and processing:

People:

- Unfortunately, most informal waste pickers remain invisible. Between 1.5 and 4 million waste pickers in India work without social security, health insurance, minimum wages or basic protective gear.

- For decades, waste pickers, working in dangerous and unsanitary conditions, have picked up what we throw away.

- They form the base of a pyramid that includes scrap dealers, aggregators and re-processors. This pyramid has internalised the plastic waste management costs of large producers.

- Besides, by diverting waste towards recycling and reuse, waste pickers also subsidise local governments responsible for solid waste management.

- Further, they reduce the amount of waste accumulating in cities, water bodies and dumpsites and increase recycling and reuse, creating environmental and public health benefits.

- This is akin to dispossessing waste pickers of their means of livelihood as all plastic waste, contributing up to 60% of their incomes, will likely be siphoned away from them and channelised into the new chain.

- Without strong government regulation, the millions of workers who have shouldered the burden of waste management for decades will stand to lose their livelihoods – only so that companies can keep meeting their targets to continue producing plastic.

Regarding the Plastics:

- Plastic packaging can be roughly grouped into three categories: recyclable and effectively handled by the informal sector, technologically recyclable but not economically viable to recycle, technologically challenging to recycle (or non-recyclable).

- Rigid plastics like PET and HDPE are effectively recycled. In keeping with the EPR objective that all recyclable plastics are effectively recycled at the cost of the producer, the government could support and strengthen the informal recycling chain by bridging gaps in adequate physical spaces, infrastructure, etc.

- The EPR guidelines are limited to plastic packaging. While a large part of plastics produced are single-use or throwaway plastic packaging, there are other multi-material plastic items like sanitary pads, chappals, and polyester that pose a huge waste management challenge today, but have been left out of the scope of EPR.

- Market value for the flexible plastics can be increased by increasing the demand for and use of recycled plastics in packaging, thus creating the value to accommodate the current costs of recycling.

- The mandated use of recycled plastics, as prescribed in the draft regulations, is a strong policy mechanism to create this value.

- Multi-layered and multi-material plastics form the abundant type of plastic waste. These are low weight and voluminous, making them expensive to handle and transport.

- Since they are primarily used in food packaging, they often attract rodents, making storage problematic.

- Even if this plastic is picked, recycling is technologically challenging as it is heterogeneous material.

- The Plastic Waste Management Rules mandated the phase-out of these plastics. However, in 2018, this mandate was reversed.

Processing:

- A 2019 report by the Center for International Environmental Law suggests that by 2050, Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions from plastic could reach over 56 gigatonnes, 10-13% of the remaining carbon budget.

- Not all processing is recycling. Processes like waste-to-energy, co-processing and incineration have been proven to release carbon dioxide, particulate matter, harmful dioxins and furans which have negative climate and health impacts.

- Technologies like chemical recycling and pyrolysis are capital-intensive, yielding low returns and running into frequent breakdowns and technological problems. They also release carbon dioxide and other pollutants.

- These end-of-life processes are economically, environmentally and operationally unsustainable.

- A number of gasification, pyrolysis and other chemical recycling projects have figured in accidents such as fires, explosions and financial losses.

- While the environmental impact and desirability of these processes continues to be debated, the draft regulations legitimise them to justify the continued production of multi-layered plastics.

Way Ahead:

- EPR funds could be deployed for mapping and registration of the informal sector actors, building their capacity, upgrading infrastructure, promoting technology transfer, and creating closed loop feedback and monitoring mechanisms.

- For easily recycled plastics, EPR requirements could have been fulfilled by formalising and documenting the work of the informal sector and adequately compensating them.

- Citizens have to bring behavioral change and contribute by not littering and helping in waste segregation and waste management.

Conclusion:

The government should redo the consultation process for the draft guidelines and involve informal workers.

The scope of plastics covered by the guidelines could be altered to exclude those plastics which are already efficiently recycled and to include other plastic and multi-material items.

An effective EPR framework should address the issue of plastics and plastic waste management in tandem with the existing machinery, minimise duplication and lead to a positive environmental impact, with monitoring mechanisms including penalties for non-compliance.

And end-of-life processing technologies should be closely evaluated, based not only on their health and environmental impacts, but also on the implications for continued production of low-quality and multi-layered plastics.

[ad_2]