[ad_1]

Context:

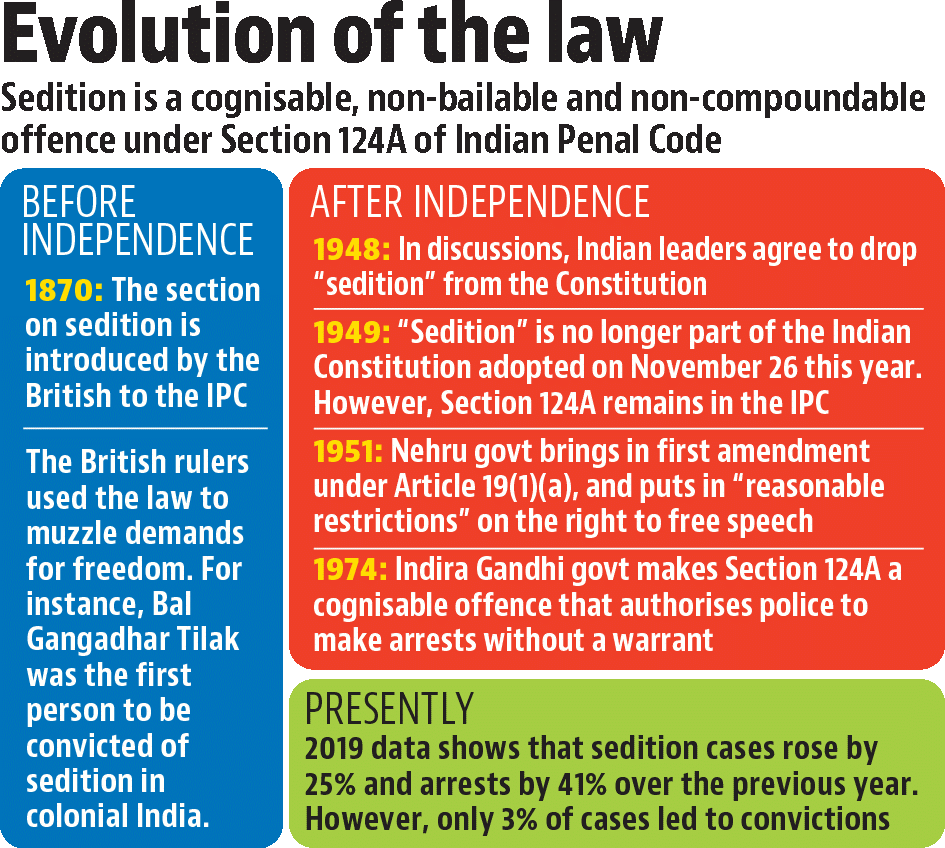

As many as three benches in the Supreme Court have recently underscored the need to review Section 124A (sedition) in the Indian Penal Code (IPC), making it pertinent to examine how the penal law has evolved since the pre-Independence era and the interpretations rendered to it by the constitutional courts in the country.

Proceedings in the Supreme Court and the contentious arrests of activists and journalists have once again brought the law of sedition into the spotlight.

The colonial era law, which many say is used to quell protests and to quieten criticism against the government, carries a maximum punishment of life imprisonment and the police can arrest individuals without a warrant.

The law has been amended after Independence, but only to make it more stringent.

History of sedition law in India:

- India’s sedition law has an interesting past. IPC was brought into force in colonial India in 1860 but had no section concerning sedition.

- The law was originally drafted in 1837 by Thomas Macaulay, the British historian-politician, but was inexplicably omitted when the Indian Penal Code (IPC) was enacted in 1860.

- Section 124A was inserted in 1870 by an amendment introduced by Sir James Stephen when it felt the need for a specific section to deal with the offence.

- It was one of the many draconian laws enacted to stifle any voices of dissent at that time.

- Under Section 124A of IPC, the offence of sedition is committed when any person by words or otherwise brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the government established by law.

Use of sedition in the British Raj:

- The penal provision came in handy to muzzle nationalist voices and demands for freedom.

- The long list of India’s national heroes who figured as accused in cases of sedition includes Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Mahatma Gandhi, Bhagat Singh and Jawaharlal Nehru.

- Bal Gangadhar Tilak was the first person to be convicted of sedition in colonial India.

- The British government brought the charge alleging articles carried in Tilak’s Marathi newspaper Kesari would encourage people to foil the government’s efforts at curbing the plague epidemic in India.

- In 1897, Tilak was punished by the Bombay high court for sedition under Section 124A and was sentenced to 18 months in prison.

- Tilak was held guilty by a jury composed of nine members, with the six white jurors voting against Tilak, and three Indian jurors voting in his favour.

- Later, Section 124A was given different interpretations by the Federal Court, which began functioning in 1937, and the Privy Council that was the highest court of appeal based in London.

Sedition cases up in India but convictions dip:

- According to the data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), uploaded on its website, cases of sedition and under the stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act showed a rise in 2019, but only 3% of the sedition cases resulted in convictions.

- The year 2019 saw a 25% increase in the number of sedition cases and a 41% increase in arrests over the previous year.

- A total of 93 cases of sedition were reported in 2019, with 96 arrests and charge sheets filed in 76 cases, as against 70 cases, 56 arrests and 27 charge sheets the previous year.

- The ministry of home affairs, in a written reply informed the Rajya Sabha that out of the 96 people arrested for sedition in 2019, only two were convicted for the crime, while 29 were acquitted.

Not a reasonable restriction:

- The section does not get protection under Article 19(2) on the ground of reasonable restriction.

- It may be mentioned in this context that sedition as a reasonable restriction, though included in the draft Article 19 was deleted when that Article was finally adopted by the Constituent Assembly.

- It clearly shows that the Constitution makers did not consider sedition as a reasonable restriction.

- However, the Supreme Court was not swayed by the decision of the Constituent Assembly.

- It took advantage of the words ‘in the interest of public order’ used in Article 19(2) and held that the offence of sedition arises when seditious utterances can lead to disorder or violence.

- This act of reading down Section 124A brought it clearly under Article 19(2) and saved the law of sedition.

- Otherwise, sedition would have had to be struck down as unconstitutional.

- Thus, it continues to remain on the statute book and citizens continue to go to jail not because their writings led to any disorder but because they made critical comments against the authorities.

Supreme Court: Sedition law needs relook, especially for media:

- The SC highlighted debates over sedition in 1950 in its decisions in Brij Bhushan vs the State of Delhi and Romesh Thappar vs the State of Madras.

- In these cases, the court held that a law which restricted speech on the ground that it would disturb public order was unconstitutional.

- In 1962, the SC decided on the constitutionality of Section 124A in Kedar Nath Singh vs State of Bihar.

- It upheld the constitutionality of sedition, but limited its application to “acts involving intention or tendency to create disorder, or disturbance of law and order, or incitement to violence”.

- In 1995, the SC, in Balwant Singh vs State of Punjab, held that mere sloganeering which evoked no public response did not amount to sedition.

Impacting rights:

In the ultimate analysis, the judgment in Kedar Nath which read down Section 124A and held that without incitement to violence or rebellion there is no sedition, has not closed the door on misuse of this law.

It says that ‘only when the words written or spoken etc. which have the pernicious tendency or intention of creating public disorder’ the law steps in.

So, if a policeman thinks that a cartoon has the pernicious tendency to create public disorder, he will arrest that cartoonist.

It is the personal opinion of the policeman that counts. The Kedar Nath judgment makes it possible for the law enforcement machinery to easily take away the fundamental right of citizens.

Conclusion:

Section 124A should not be misused as a tool to curb free speech.

The SC caveat, given in KedarNath case, on prosecution under the law can check its misuse.

It needs to be examined under the changed facts and circumstances and also on the anvil of ever-evolving tests of necessity, proportionality and arbitrariness.

In a democracy, people have the inalienable right to change the government they do not like. People will display disaffection towards a government which has failed them.

The law of sedition which penalises them for hating a government which does not serve them cannot exist because it violates Article 19(1)(a) and is not protected by Article 19(2).

Therefore, an urgent review of the Kedar Nath judgement by a larger Bench has become necessary.

[ad_2]