[ad_1]

Context:

In the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic, PM Modi once again brought up the much-discussed issue of reforming the World Health Organization while addressing the heads of countries at the second global COVID-19 summit.

PM Mr. Modi has been right in calling for reforms in WHO, the demand for a review of the health agency’s processes on vaccine approvals is far removed from reality.

Reforms needed to maintain better Global Health Body:

- That reforms are urgently needed to strengthen the global health body and its ability to respond to novel and known disease outbreaks in order to limit the harm caused to the global community is beyond debate.

- The long delay and the reluctance of China to readily and quickly share vital information regarding the novel coronavirus, including the viral outbreak in Wuhan, and its stubborn refusal to allow the global agency to investigate, freely and fairly, the origin of the virus have highlighted the need to strengthen WHO.

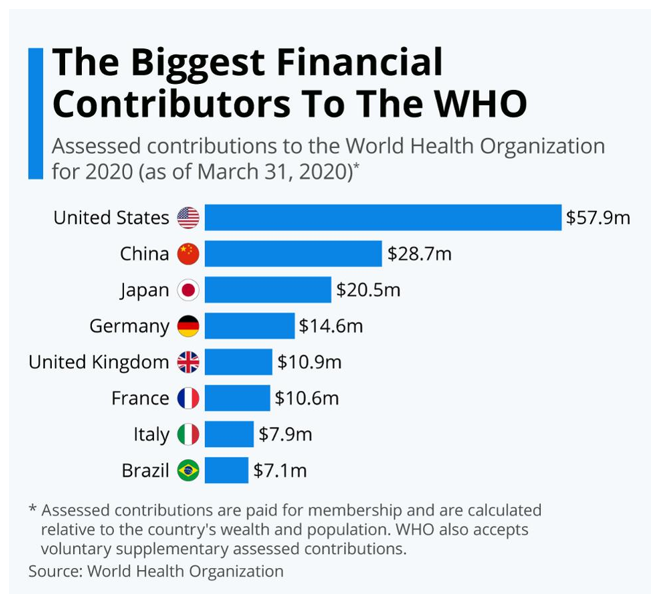

- But any attempt to build a stronger WHO must first begin with increased mandatory funding by member states.

- For several years, the mandatory contribution has accounted for less than a fourth of the total budget, thus reducing the level of predictability in WHO’s responses; the bulk of the funding is through voluntary contribution.

- Importantly, it is time to provide the agency with more powers to demand that member states comply with the norms and to alert WHO in case of disease outbreaks that could cause global harm.

- Under the legally binding international health regulations, member states are expected to have in place core capacities to identify, report and respond to public health emergencies.

- Ironically, member states do not face penalties for non-compliance. This has to change for any meaningful protection from future disease outbreaks.

Emergency Use Listing (EUL) of Covaxin:

- Covaxin is not the first vaccine from India to be approved by WHO, and the manufacturer of this vaccine has in the past successfully traversed the approval processes without any glitch.

- The demand for a review of the vaccine approval process is based on the assumption that the emergency use listing (EUL) of Covaxin was intentionally delayed by the health agency, which has no basis.

- That the technical advisory group had regularly asked for additional data from the company only underscores the incompleteness of the data presented by the company.

- As a senior WHO official said, the timeline for granting an EUL for a vaccine depends “99% on manufacturers, the speed, the completeness” of the data.

- To believe that the agency was influenced more by media reports than the data submitted by the company is naive;

- The media were only critical of the Indian regulator approving the vaccine even in the absence of efficacy data.

- Any reform in WHO should not dilute the vaccine approval process already in place.

India submits 9-point plan for WHO reforms:

- India has proposed a nine-point plan for reforms of the World Health Organization (WHO), including changes in mechanisms to monitor health emergencies that can cross borders and giving the head of the UN body greater power to declare an international public health emergency.

- The proposals, which have been formally conveyed to UN and WHO authorities, also include changes and improvements in the body’s funding and governance, transparency in use of funds, and a greater role for the world body in ensuring fair, affordable and equitable access to Covid-19 vaccines.

- The Indian government has repeatedly raised the need to reform WHO at multilateral forums such as the G20 and BRICS this year, and Prime Minister Modi criticized the body for not reflecting contemporary realities.

- India’s calls for WHO reforms, especially after the body’s initial handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, have been backed by countries around the world.

- The Indian government’s proposals, contained in the document “Approach on WHO reforms”, call for devising “objective criteria with clear parameters” for declaring a “public health emergency of international concern” (PHEIC) such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

- The WHO director general currently has to convene a committee of experts, the International Health Regulations (IHR) Emergency Committee, to declare an international emergency.

- India has proposed the WHO chief should be empowered to declare a PHEIC if there is “broad agreement, though not a consensus” within the emergency committee.

- The emphasis must be on transparency and promptness in the declaration process.

- The Indian recommendation is relevant in view of WHO’s regulations which state the emergency committee gives advice on declaration of a PHEIC when there is “inconsistency in the assessment of the event” between the WHO chief and the affected country – something that revelations have pointed to in the case of Covid-19.

Indian government: extra-budgetary contributions:

- The Indian government pointed out that most of the financing for WHO’s programmes comes from extra-budgetary contributions earmarked for specific issues.

- Since WHO has little flexibility in using these funds, voluntary contributions should be “unearmarked to ensure that the WHO has necessary flexibility for its usage in areas where they are required the most”, it recommended.

- The Indian government also called for efforts to “ensure fair, affordable and equitable access to all tools for combating Covid-19 pandemic and, therefore, the need to build a framework for their allocation”.

- WHO’s work in this direction should be supported, and Covid-19 vaccines are a “global public good and TRIPS waiver as proposed by India and South Africa would go a long way in effective international and national response” to the pandemic.

- It also pointed out that “as a reflection of vaccine nationalism, some developed countries have been signing bilateral agreements with vaccine manufacturers, leaving very little space for developing countries to get fair, affordable and equitable access” to vaccines.

- India was elected to WHO’s Executive Board and will chair the body during 2020-21, putting it in a position to suggest key reforms to the body.

- Calling for a global framework for managing infectious diseases and pandemics, including capacities such as testing and surveillance systems, the document highlighted the “need to establish a system facilitating pan-world surveillance by leveraging innovating ICT tools”.

Conclusion:

The discussion of WHO’s evolution and efforts to reform it covers a very wide range of topics concerning governance, structure, policies, priorities, financing and management.

The intention was to provide background and historical perspective relevant to current discussions of WHO reform.

The current reform process within WHO is in many ways admirably comprehensive but for understandable reasons there are various potential avenues for reform that are not fully addressed.

The current process does not ask fundamental questions about WHO’s place in the international system for health as it has now evolved, nor whether WHO’s governance, management and financing structures need more fundamental change than is currently envisaged.

It is therefore unclear whether the latest reform efforts will be sufficient to enable the organization to fulfil its potential.

[ad_2]