[ad_1]

Context:

After many years of refusing to recognise there is a jobs crisis in India, the government of India, faced with relentless data to the contrary, has now resorted to misinformation.

Regrettably, both pieces show an inadequacy in understanding the jobs situation.

NSO’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS):

As compared to the 8% per annum GDP growth in the period 2004-14, and 7.5 million new non-farm jobs created each year over 2005 to 2012 (NSO’s employment-unemployment survey), the number of new non-farm jobs generated between 2013-2019 was only 2.9 million, when at least 5 million were joining the labour force annually (NSO’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS)).

The NSO itself states clearly that the two surveys provide comparable data; the claim that those two surveys are not comparable is not correct.

Unpaid Family Labour:

- A claim is made that between 2017-18 and 2019-20, the worker participation rate (WPR) and labour force participation rate (LFPR) is rising, showing improvement in the labour market.

- The reality is that this rise in WPR and LFPR is misleading. It was caused mostly by increasing unpaid family labour within self-employed households, mostly by women.

- The claim that manufacturing employment increased between 2017-18 and 2019-20 by 1.8 million is technically correct (based on PLFS).

- What this ignores is that between 2011-12 and 2017-18, manufacturing employment fell in absolute terms by 3 million, so a recovery is hardly any consolation.

- Manufacturing as a share of GDP fell from 17% in 2016 to 15%, then 13% in 2020, despite ‘Make in India’.

Stagnation in manufacturing output and employment and contraction of the labor-intensive segment of the formal manufacturing sector:

- Excess rigidity in the formal manufacturing labour market and rigid labour regulations has created disincentives for employers to create jobs.

- Industrial Disputes Act has lowered employment in organized manufacturing by about 25% (World Bank Study).

- Stringent employment protection legislation has pushed employers towards more capital-intensive modes of production than warranted by existing costs of labour relative to capital.

- Therefore, the nature of the trade regime in India is still biased towards capital-intensive manufacturing.

India seems to be witnessing a joblessness crisis:

- The number of new non-farm jobs generated between 2013- 2019 was only 2.9 million, when at least 5 million were joining the labour force annually (NSO’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS)).

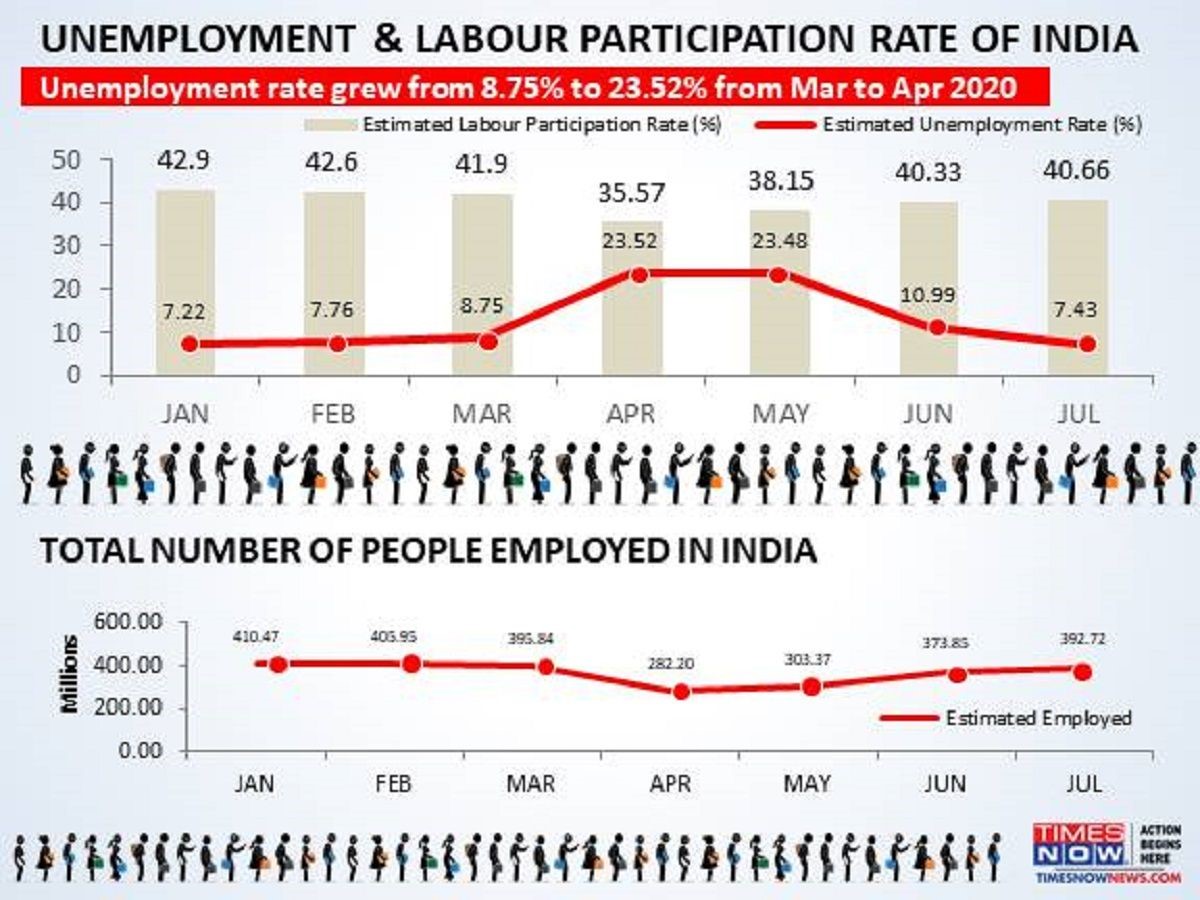

- There has been a massive increase in joblessness of at least 10 million due to COVID-19, on top of the 30 million already unemployed in 2019.

- There has been a negative growth in manufacturing employment between 2011 and 2020 despite schemes like ‘Make in India’.

- As against the claim that between 2017-18 and 2019-20, the worker participation rate (WPR) and labour force participation rate (LFPR) was rising, showing improvement in the labour market, this rise was caused mostly by increasing unpaid family labour, mostly by women.

- MSMEs which are employment-intensive have been hit hard by the pandemic. This does not augur well for non-farm employment generation in India.

As against the progressive structural change trend of reducing the proportion of the population indulged in agriculture and allied activities with time, in India between 2019 and 2020, the absolute number of workers in agriculture increased from 200 million to 232 million. This resulted in the depressing of rural wages.

Farm employment:

- In any case, the recovery of urban employment till March 2021 clearly ignores that urban employment barely captures a third of total employment.

- Besides, agriculture output may have performed well during COVID, and free rations may have alleviated acute distress.

- This completely ignores that between 2019 and 2020, the absolute number of workers in agriculture increased from 200 million to 232 million, depressing rural wages — a reversal of the absolute fall in farm employment of 37 million between 2005-2012, when non-farm jobs were growing 7.5 million annually, real wages were rising, and number of poor falling.

- Rising farm employment is a reversal of the structural change underway until 2014.

Issue of New EPFO data need to look in:

Another dubious argument is offered to supplement the claim that organized formal employment is rising, because new registration in employment provident fund rose in the last two years.

One limitation of EPFO-based payroll data is the absence of data on unique existing contributors.

Employees join, leave and then rejoin leading to large and continuous revisions in EPFO enrolment.

There has been a massive increase in joblessness of at least 10 million due to COVID-19, on top of the 30 million already unemployed in 2019.

This happened while the CMIE is reporting the employment rate has fallen from nearly 43% in 2016 to 37% in just four years.

Conclusion:

India needs a new strategy to counter the phenomena of jobless growth. This requires manufacturing sector to play a dominant role.

“MAKE IN INDIA” initiative a great step forward which will boost the manufacturing.

Decentralisation of Industrial activities is necessary so that people of every region get employment.

Development of the rural areas will help mitigate the migration of the rural people to the urban areas thus decreasing the pressure on the urban area jobs.

Complementary schemes like Skill India, Startup India etc. can enhance the skillsets and employment generation

[ad_2]