[ad_1]

Introduction:

The makers of the Constitution of India did not anticipate that the office of the Governor, meant to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution and the law”, would metamorphose into the most controversial constitutional office rendering the constitutional praxis rugged.

Though the original Draft of the Constitution provided for either the direct election or the appointment of the Governor (Article 131 of the draft which was to become Article 155).

But the Constituent Assembly chose a third alternative for the appointment of the Governor by the President, so as to avoid confrontation with the elected executive.

Governor post: Nomination provision rather than elected:

- Article 131 of the draft Constitution had provided for an elected Governor or a Governor appointed by the President from a panel of four candidates elected by the Legislative Assembly.

- After elaborate deliberations, the Constituent Assembly voted for a nomination provision which rules out any role for the Legislative Assembly.

- Jawaharlal Nehru also strongly supported a nominated Governor as an elected Governor may lead “to conflict and waste of energy and money and also leading to certain disruptive tendency in this big context of an elective governor plus parliamentary system of democracy.”

- Finally, a process by which the Governor is nominated by the President on the advice of the Council of Ministers was adopted and it became Article 155 of the enacted Constitution.

- When the elected Governor of the United States was juxtaposed with the nominated Governor in Canada and Australia, democratic propriety demanded nomination despite the suspicious reluctance towards the parent law, the Government of India Act, 1935, which conceived the nomination system.

Politics till the Bommai verdict:

- A classic example of Raj Bhavan getting embroiled in partisan politics was sketched by a series of events in Tamil Nadu beginning from the declaration of national emergency on June 25, 1975.

- This was followed by the DMK regime offering political support and shelter to the national dissidents which led to realignments in State politics.

- A report was then sent by the then Governor K. K. Shah seeking the dismissal of the DMK government for pervasive corruption and therefore, President’s Rule was imposed on February 3, 1976.

- The President’s Rule was imposed in States over a 100 times prior to 1994.

- But after the Supreme Court’s judgment in the S. R. Bommai case, such rampant practices came to an end as the Supreme Court declared that the imposition of President’s Rule shall be confined only to the breakdown of constitutional machinery.

The Sarkaria Vision:

The S.R. Bommai judgment passed by the nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court extensively quoted from the commission on Centre-State Relations constituted by Central Government in 1983.

The three-member commission headed by Justice R. S. Sarkaria remains till date the bedrock of any inquiry into the relations between the Centre and State.

The Commission, which submitted its report in 1988, sought to reinfuse the spirit of co-operative federalism in Indian politics.

Recommendations of Sarkaria Commission:

- The Sarkaria Commission sought to restore dignity to the Raj Bhavan by focusing more on the appointee who shall be an eminent person in some walk of life, someone outside the respective State so that he would not have any personal interest to protect.

- The Commission reiterated the views of Nehru as expressed on the floor of the Constituent Assembly that it is “better to have a detached figure” as Governor who has not been recently active in politics.

- While batting for a secure term for the Governor, the Commission condemned the practice of Governors venturing further into active politics as well as ascending to other offices after the completion of the term, all of which contaminate the purity of gubernatorial intent.

- Regarding the Governor’s role as the Chancellor of State universities, the Sarkaria Commission was of the view that it is desirable to consult the Chief Minister or the concerned minister, though it shall be left to the Governor to act on the same or not.

Administrative Reforms Commission reports on appointment as Governor:

- As a matter of fact, the first Administrative Reforms Commission (1966) in its report on “Centre-State Relationships” had recommended strongly that once the Governor completes his term of five years, he shall not be made eligible for further appointment as Governor.

- Unlike the Sarkaria Commission which was specifically on Centre State Relations, the mandate and canvas of the Administrative Reform Commission (ARC) was wider.

- Nevertheless, the limited views offered by the ARC testifies the formative concern of Indian polity on the politicisation of the office of the Governor.

- The National Commission (2000) also reiterated the view of the Sarkaria Commission regarding the appointment of Governor.

- It enriched the discourse by stipulating that there should be a time-limit, desirably six months to give assent or to reserve a Bill for consideration of the President.

- If the Bill is reserved for consideration of the President, there should be a time-limit, desirably of three months, within which the President should take a decision whether to accord his assent or to direct the Governor to return it to the State Legislature or to seek the advisory opinion of the Supreme Court.

The Punchhi Commission affirmed the recommendations of the Sarkaria Commission:

- The Punchhi Commission on Centre-State relations (2007), headed by former Chief Justice of India Justice M. M. Punchhi, was constituted to enquire into Centre-State Relations taking into account the changes in the last years since Sarkaria Commission submitted its report in 1988.

- Though Punchhi Commission affirmed most of the recommendations of the Sarkaria Commission, its views also reflected the changing times and its needs.

- The Commission could not appreciate the practice of Governors being called back at the bell of regime change, something that does not befit the salutary position assigned to the Governor.

- It must be remembered that a constitution bench of the Supreme Court in the P. Singhal Case (2010) declared that a change in power at the Centre cannot be grounds to recall governor and hence such actions are judicially reviewable.

- While Sarkaria Commission recommended that Governor’s tenure of five years shall only be sparingly cut short, Punchhi Commission went one step ahead and recommended that Governor shall have fixed tenure so that they wouldn’t hold office under the intangible pleasure of the Central government.

- It proposed an amendment to Article 156 so that there would be a procedure to remove the Governor from office.

- It also went further in recommending that Governors shall not be overburdened with the task of running universities by virtue of them being made Chancellors under the State University Acts.

- Complying with the norms and conventions advocated by the Sarkaria commission coupled with the functional safeguards recommended by the Punchhi Commision will go a long way in rediscovering the constitutional equilibrium.

Conclusion:

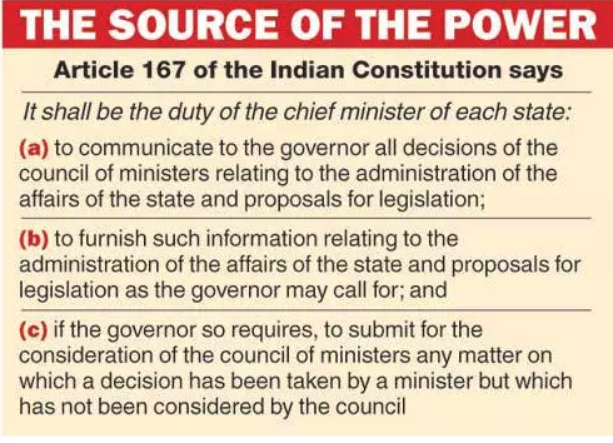

Dr. Ambedkar categorically stated on the floor that “The Governor under the Constitution has no functions which he can discharge by himself; no functions at all. While he has no functions, he has certain duties to perform…”

Instead of a powerful Governor, what the Constitution conceived was a duty-bound Governor, a constitutional prophesy that failed to work.

[ad_2]