[ad_1]

Context:

Of a total of ₹981.98 crore sanctioned in 2019-20 under the Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS) to the States and Union Territories for development of infrastructure in the courts, only ₹84.9 crore was utilised by a combined five States, rendering the remaining 91.36% funds unused.

This underutilization of funds is not an anomaly induced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The issue has been plaguing the Indian judiciary for nearly three decades when the CSS was introduced in 1993-94.

This is one of the reasons why the Chief Justice of India recently proposed creation of a National Judicial Infrastructure Authority of India (NJIAI), which will take control of the budgeting and infrastructure development of subordinate courts in the country.

Good judicial infrastructure for courts in India has always been an afterthought. It is because of this mindset that courts in India still operate from dilapidated structures making it difficult to effectively perform their function.

In Judiciary, Lack of Human Power:

- The posts in the judiciary are not filled up as expeditiously as required.

- The process of judicial appointment is delayed due to delay in recommendations by the collegium for the higher judiciary.

- Delay in recruitment made by the state commission/high courts for lower judiciary is also a cause of the poor judicial system.

- The judge-population ratio in the country is not very appreciable.

- While for the other countries, the ratio is about 50-70 judges per million people, in India it is 20 judges per million heads.

- It is only since the pandemic that the court proceedings have started to take place virtually too, earlier the role of technology in the judiciary was not much larger.

Harsh situation in Judiciary: State of infrastructure:

- The Indian judiciary’s infrastructure has not kept pace with the sheer number of litigations instituted every year.

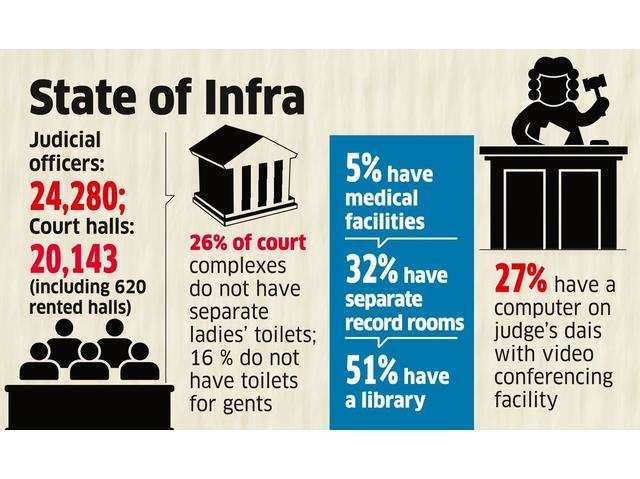

- A point cemented by the fact that the total sanctioned strength of judicial officers in the country is 24,280, but the number of court halls available is just 20,143, including 620 rented halls.

- Also, there are only 17,800 residential units, including 3,988 rented ones, for the judicial officers.

- As much as 26% of the court complexes do not have separate ladies toilets and 16% do not have gents toilets.

- Only 32% of the courtrooms have separate record rooms and only 51% of the court complexes have a library.

- Only 5% of the court complexes have basic medical facilities and, only 51% of the court complexes have a library.

- While the pandemic has forced most of the courts to adopt a hybrid system, physical and videoconferencing mode of hearing, only 27% of the courtrooms have a computer placed on the judge’s dais with videoconferencing facility.

Greater autonomy for Judiciary is the need of the hour:

- Chief Justice of India, in his speech at the event, highlighted that the improvement and maintenance of judicial infrastructure is still being carried out in an ad-hoc and unplanned manner.

- He stressed on the need for “financial autonomy of the judiciary” and creation of the NJIAI that will work as a central agency with a degree of autonomy.

- Explaining the requirement for a greater autonomy for the NJIAI, a source familiar with the development in the Supreme Court, said, “The lack of one particular coordinating agency means each year the funds get lapsed. It remains underutilized.”

- This claim is supported by the fact that in 2020-21, of the ₹594.36 crore released under the CSS, only ₹41.28 crore was utilised by a single State, Rajasthan.

- The data released by the Department of Justice further revealed that in 2018-19, of the ₹650 crore released by the Centre under the CSS, the utilisation certificate was submitted by 11 States for a total of ₹225 crore.

- The current fund-sharing pattern of the CSS stands at 60:40 (Centre:State) and 90:10 for the eight north-eastern and three Himalayan States. The Union Territories get 100% funding.

- There has to be a special purpose vehicle driven by a sense of belongingness and passion, with a degree of authority. That authority has to come from the Supreme Court.

NALSA model for Judicial Infrastructure:

- The proposed NJIAI could work as a central agency with each State having its own State Judicial Infrastructure Authority, much like the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) model.

- It has also been suggested that the Chief Justice of India could be the patron-in-chief of the NJIAI, like in NALSA, and one of the Supreme Court judges nominated by the Chief Justice could be the executive chairman.

- But, unlike NALSA which is serviced by the Ministry of Law and Justice, the proposed NJIAI should be placed under the Supreme Court of India.

- In the NJIAI there could be a few High Court judges as members, and some Central Government officials because the Centre must also know where the funds are being utilised.

- Similarly, in the State Judicial Infrastructure Authority, in addition to the Chief Justice of the respective High Court and a nominated judge, four to five district court judges and State Government officials could be members.

- The Chief Justice is mindful of the fact that the High Courts are independent of the Supreme Court.

- The only time when the Supreme Court comes in the picture is the appointment of judges of the High Courts.

‘Funding, executing & supervisory agency for development’:

- While the NJIC will be the nodal agency for infrastructural developments, it will not be involved in judicial appointments in trial courts. Appointments will continue to be made by the state governments and the respective high courts.

- The NJIC will be a funding, executing and supervisory agency for development works.

- According to the CJI’s proposal, both the central and state governments will contribute their share of funds outlined in the centrally-sponsored scheme to the NJIC, which will then release the finances to the high court’s according to their requirement.

- The structure of the corporation is likely to be modelled on the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA), a national body based in Delhi that provides free legal services.

- At the national level, the CJI will be the patron of the NJIC, which will include two senior SC judges, the finance secretary from the central government, two to three senior chief justices of state HCs, and a member of the Niti Aayog.

- Each state is likely to have a local corporation as well, which will be led by the state HC chief justice along with a senior judge and senior state government bureaucrats.

- This composition will also ensure regular interaction between the two stakeholders – judiciary and the executive – over improving court infrastructure.

Conclusion:

The NJIC will not suggest any major policy change but will give complete freedom to HCs to come up with projects to strengthen ground-level courts.

It may recommend a model structure of how a court complex, courtroom or a waiting area for litigants should be. However, it will be up to the high courts to adopt and modify the suggestions according to their requirements.

Institutionalizing the mechanism for augmenting and creating state-of-the-art judicial infrastructure is the best gift that we can think of giving to our people and our country in this 75th year of our Independence.

[ad_2]