[ad_1]

Introduction:

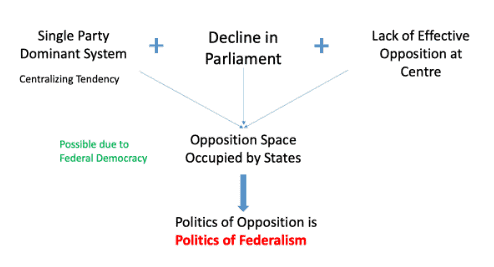

Federalism in India has always had political relevance, but except for the States Reorganisation Act, federalism has rarely been an axis of political mobilisation.

This was true even in the days of coalition politics when State politics mattered to national electoral outcomes.

Recently, several states have complained about the growing crisis of Indian federalism.

They have argued about the Ordinances and the Bills brought by the Centre which encroaches on their area of legislation, which is an assault on the federal structure of the Constitution.

Creating a political consensus for genuine federalism:

- Fiscal and administrative centralisation persisted despite nearly two decades of coalition governments.

- Ironically, rather than deepen federalism, the contingencies of electoral politics have created significant impediments to creating a political consensus for genuine federalism.

- When confronted with entrenched centralisation of the present regime, the challenge is, ironically, even greater.

- Between vaccine wars, heated debates over the Goods and Services Tax (GST), personnel battles like the fracas over West Bengal’s Chief Secretary, and the pushback against controversial regulations in Lakshadweep, is India ready for a new federal bargain?

Constitutional Provisions Related to Federalism:

- Elements of federalism were introduced into modern India by the Government of India Act of 1919 which separated powers between the centre and the provincial legislatures.

- The respective legislative powers of states and Centre are traceable to Articles 245 to 254.

- The Seventh Schedule of the Constitution contains three lists that distribute power between the Centre and states (Article 246).

- There are 98 subjects (originally 97) in the Union List, on which Parliament has exclusive power to legislate.

- The State List has 59 subjects (originally 66) on which states alone can legislate.

- The Concurrent List has 52 subjects (originally 47) on which both the Centre and states can legislate. In case of a conflict, the law made by Parliament prevails (Article 254).

- Article 1 of the Constitution mentions that India that is Bharat shall be a Union of States. It means that states do not have power or right to secede away from the Union of India. Also unlike USA, in India, different states have not formed because of an agreement among the states.

- Article 3 of the Constitution empowers Parliament to create new States. It allows the federation to evolve, grow and respond to regional aspirations.

- When a new state is formed, Schedule I and Schedule IV of the Constitution shall be amended.

- Schedule I – contains list of States and Union Territories

- Schedule IV – provides for allocation of seats in Rajya Sabha. The allocation of seats in Rajya Sabha is made on the basis of the population of each State.

However, problems existing are:

Divide among States: A real impediment to collective action:

- The increased economic and governance divergence between States.

- Economic growth trajectories since liberalisation have been characterised by growing spatial divergence.

- Across all key indicators, southern (and western) States have outperformed much of northern and eastern India resulting in a greater divergence rather than expected convergence with growth.

- This has created a context where collective action amongst States becomes difficult as poorer regions of India contribute far less to the economy but require greater fiscal resources to overcome their economic fragilities.

- Glimpses of these emerging tensions were visible in the debates around the 15th Finance Commission (FC) when the Government of India mandated the commission to use the 2011 Census rather than the established practice of using the 1971 Census to determine revenue share across States.

- This, Southern states feared, risked penalising States that had successfully controlled population growth by reducing their share in the overall resource pool.

- The 15th Finance Commission, through its recommendations, deftly avoided a political crisis but the growing divergence between richer and poorer States, remains an important source of tension in inter-State relations that can become a real impediment to collective action amongst States.

- With the impending delimitation exercise due in 2026, these tensions will only increase.

Fiscal management by the states:

- The realities of India’s macro-fiscal position risk increasing the fragility of State finances.

- Weak fiscal management has brought the Union government on the brink of what economist Rathin Roy has called a silent fiscal crisis.

- The Union’s response has been to squeeze revenue from States by increasing cesses.

- Its insistence on giving GST compensation to States as loans (after long delays) and increasing State shares in central schemes. The pandemic-induced economic crisis has only exaggerated this.

- Against this backdrop, if harnessed well, both sub-nationalist sentiments and the need to reclaim fiscal federalism create a political moment for a principled politics of federalism.

- An effort at collective political action for federalism based on identity concerns will have to overcome this risk.

- On the fiscal side, richer States must find a way of sharing the burden with the poorer States.

- States will have to show political maturity to make necessary compromises if they are to negotiate existing tensions and win the collective battle with the Union.

- An inter-State platform that brings States together in a routine dialogue on matters of fiscal federalism could be the starting point for building trust and a common agenda.

- The seeds of this were planted in the debates over the 15th Finance Commission and the GST.

Conclusion:

Finally, beyond principles, a renewed politics of federalism is also an electoral necessity.

No coalition has succeeded, in the long term, without a glue that binds it.

Forging a political consensus on federalism can be that glue. But this would require immense patience and maturity from regional parties.

Our focus must continue to be on successfully engaging with health, food security and livelihood issues.

The democratic capability of the Indian state will be tested with each new wave of the pandemic.

Collaborative federalism that chooses to ignore asymmetries in power will only strengthen the democratic choices for better governance.

Cooperation between the Centre and States is key to success and the fight would very much depend upon the availability of resources.

[ad_2]