[ad_1]

Context:

A recent ruling by Rajasthan’s power regulator points to this yawning gap, but also suggests solutions that other States could emulate.

The Rajasthan Electricity Regulatory Commission (RERC) has ordered the State’s three power distribution companies, or DISCOMS (the Jaipur, Ajmet and Jodhpur Vidyut Vitran Nigam Limited) to solarise unelectrified public schools.

This has the potential to electrify about 1,500 government-run schools in the remote parts of the State with roof-top solar panels and generate about 15 megawatts (MW) of power.

The RERC has also suggested installation of batteries to ensure storage of power.

Achieving a target:

- In 2019, Rajasthan set itself an ambitious target of producing 30 GW of solar energy by 2025 (Rajasthan government, 2019).

- It currently has an installed capacity of about 5 GW, most of which are from large-scale utility plants, or solar parks with ground-mounted panels.

- The State must install at least 7 GW every year for the next four years to achieve this target. This is not impossible, but it would require investment and installation on a war footing.

- While Rajasthan is India’s largest State in terms of land mass with vast, sparsely populated tracts available to install solar parks, bulk infrastructure of this scale is susceptible to extreme weather events.

- With climate change increasing the possibility of such events, a decentralised model of power generation would prove to be more climate resilient.

Expanding Energy Access in Rural Areas:

- Over the past decade, India has made great strides in expanding energy access in rural areas.

- Credible estimates suggest a near doubling of electrified rural households, from 55% in 2010 to 96% in 2020 (World Bank, 2021).

- However, the measure of access to power supply, has been the number of households that have been connected to the electricity grid.

- While this is a significant measure, it discounts large areas of essential and productive human activities such as public schools and primary health centres.

- And despite greater electrification, power supply is often unreliable in rural areas.

- Apart from enabling education, this ruling would benefit several other crucial aspects of rural life.

- Government schools serve as public spaces in rural areas.

- They doubled up as COVID-19 care centres in the past year and have housed villagers from extreme weather such as storms and floods, apart from turning into polling centres come election season.

- Battery storage of power ensures that they cater to children’s after-school activities.

- Schools could also extend power supply to mid-day meal kitchens, toilets, and motorised water pumps and not limit it to powering fans and lights in classrooms.

Promotion of Renewable Energy:

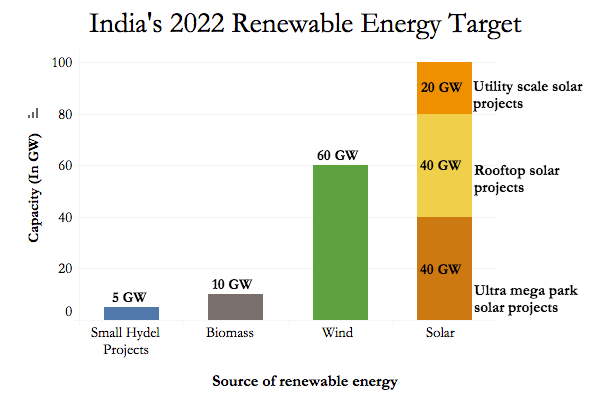

- A renewable energy capacity of 100 GW should be achieved by 2019-20 so as to contribute to achievement of 175 GW target by 2022.

- Solar Energy Corporation of India Limited (SECI) should develop storage solutions within next three years to help bring down prices through demand aggregation of both household and grid scale batteries.

- A large programme should be launched to tap at least 50% of the bio-gas potential in the country by supporting technology and credit support through NABARD by 2020.

Clean energy drive:

- The RERC order also directs Rajasthan’s cash-strapped discoms to seek corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds for the solarising drive and allows schools ownership of the power systems in a phased manner.

- This removes the burden of infrastructure development expenses on discoms, while also ensuring clean energy for the schools.

- The power that is generated could also be counted towards the discoms Renewable Purchase Obligations (RPO).

- Renewable Purchase Obligations (RPO) is the proportion of power that distribution companies must procure from renewable sources.

- This ratio is a gradual annual progression to encourage greater use of renewable energy and to provide for a phased manner to reduce dependence on climate warming fossil fuels.

Working together through CSR funds:

- One of the hurdles to holistic, climate resilient, clean energy access is the lack of convergence between government departments.

- In Rajasthan, for instance, the DISCOMS could work with the State’s Education Department to determine the schools that require electrification, and their expected demand and infrastructure expenses.

- They could then liaise with the CSR arms of companies to generate funding, and with industry to produce cost-effective solar photovoltaic panels and batteries.

- Sustaining these new power systems would require some unlearning and re-learning, but it is not unimaginable.

- Large-grid based projects add to the supply of power in urban areas, and therefore, only marginally further greater energy access goals.

- As solar installations become inexpensive and with rapidly advancing battery storage technologies, decentralised solar power generation has become a reality.

Conclusion:

Taking a cue from the RERC ruling, a greater number of public buildings could be used to install roof-top solar panels.

Buildings such as primary health centres, panchayat offices, railway stations and bus stops could easily be transitioned to utilising clean energy.

And with battery storage, the susceptibility of grid infrastructure to extreme weather events could be mitigated. This is called climate proofing.

A State such as Rajasthan, which is most exposed to solar irradiation, could set an example by making its urban and rural centres, power generators, consumers, and suppliers in the same breath.

Indeed, its government has an ambitious plan to catapult the State into being a power “exporter”, but it must consider the possibility of achieving this through means that do not destroy the environment and are most productive, cost-effective, and optimal for human activity.

[ad_2]