[ad_1]

Context:

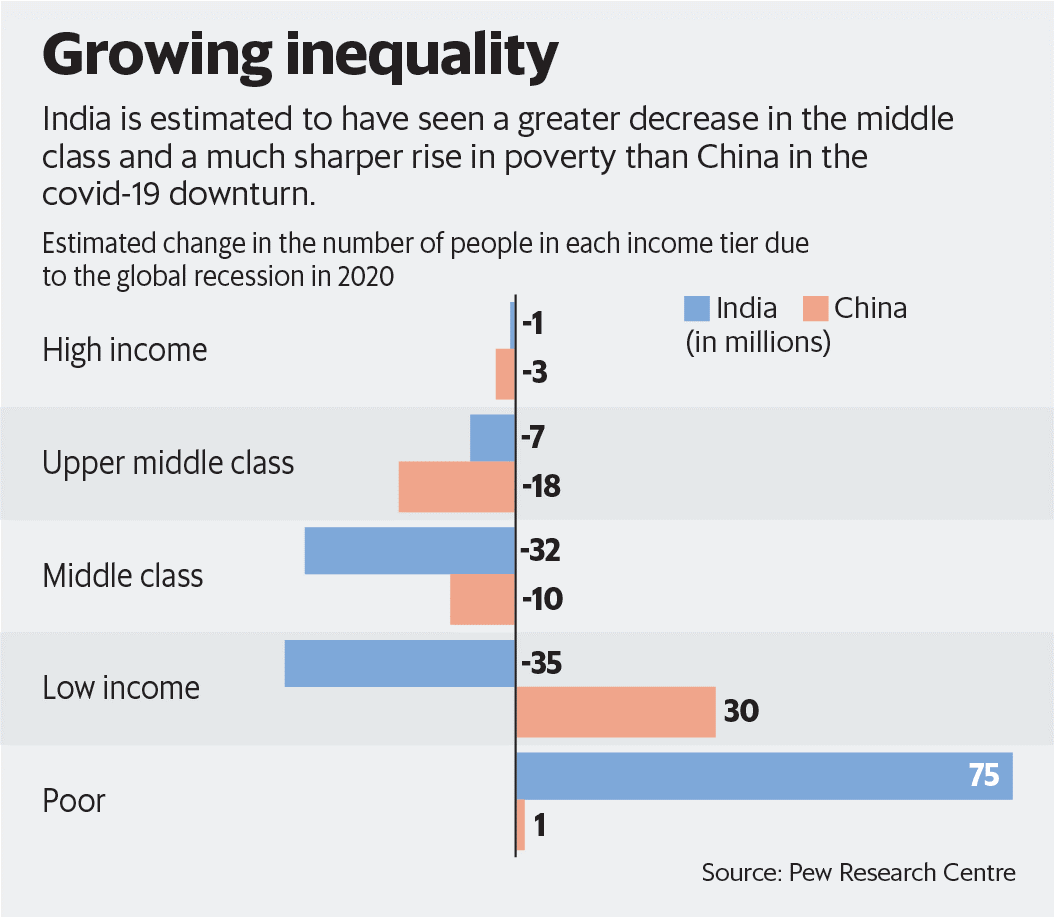

The coronavirus pandemic may have shrunk India’s middle-class population by 32 million and driven 75 million below the poverty line in 2020, a Pew Research Centre report said, as a severe recession walloped Asia’s third-largest economy.

The report, which is based on an analysis of World Bank data, said that in comparison China fared much better, with the number of people in the middle-income tier decreasing by only 10 million, while the poverty level remained virtually unchanged in 2020.

The last time that ‘India reported an increase in poverty was in the first 25 years after Independence, when from 1951 to 1974, the population of the poor increased from 47% to 56%’.

An imperative: Meticulously count poor and prioritise them:

- In India, there is now, rightly, a consensus difficult for the Government to beat down that to be able to battle COVID-19 and secure India from successive waves, the exact numbers of the dead must be carefully documented.

- Something else that needs equal attention, if the state of the decrepit Indian economy is to be repaired, is to be able to meticulously count the number of the poor and to prioritise them.

- The World Bank $2-a-day (poverty line) might be inadequate but it would be a start and higher than the last line proposed by the Rangarajan committee.

- There has been hesitation for a variety of reasons to wrestle with the rising numbers of the poor in India.

- Coming to terms with how low India’s median income is would disrupt the carefully constructed ride about being the biggest/largest in the world.

- A survey in 2013 had said India stood at 99 among 131 countries, and with a median income of $616 per annum, it was the lowest among BRICS and fell in the lower middle-income country bracket.

Due to coronavirus pandemic, concerns: India again becoming country of mass poverty

- The precarious situation after the demonetisation in 2016 was rendered calamitous with the novel coronavirus pandemic and the shrinking of the economy.

- In 2019, the global Multidimensional Poverty Index reported that India lifted 271 million citizens out of poverty between 2006 and 2016.

- Since then, the International Monetary Fund, Hunger Watch, SWAN and several other surveys show a decided slide.

- The Pew Research Center with the World Bank data estimated that ‘the number of poor in India, on the basis of an income of $2 per day or less in purchasing power parity, has more than doubled to 134 million from 60 million in just a year due to the pandemic-induced recession’.

- In 2020, India contributed 57.3% of the growth of the global poor.

- India contributed to 59.3% of the global middle class that slid into poverty.

- So, India is again a “country of mass poverty” after 45 years. This has thrown a spanner in the so far uninterrupted battle against poverty since the 1970s.

- Urgent solutions are needed within, and the starting point of that would be only when we know how many are poor.

Poverty line debate:

- According to the World Bank, Poverty is pronounced deprivation in well-being and comprises many dimensions.

- It includes low incomes and the inability to acquire the basic goods and services necessary for survival with dignity.

- Poverty Line: The conventional approach to measuring poverty is to specify a minimum expenditure (or income) required to purchase a basket of goods and services necessary to satisfy basic human needs and this minimum expenditure is called the poverty line.

- In India, the poverty line debate became very fraught in 2011, as the Suresh Tendulkar Committee report at a ‘line’ of ₹816 per capita per month for rural India and ₹1,000 per capita per month for urban India, calculated the poor at 25.7% of the population.

- The anger over the 2011 conclusions, led to the setting up of the C. Rangarajan Committee, which in 2014 estimated that the number of poor were 29.6%, based on persons spending below ₹47 a day in cities and ₹32 in villages.

Reasons why numbers count:

- The first is because knowing the numbers and making them public makes it possible to get public opinion to support massive and urgent cash transfers.

- The world outside India has moved onto propose high fiscal support, as economic rationale and not charity; it is debating a higher level of minimum wages than it has in the past.

- Spain has accorded security to its gig workers by giving delivery boys the status of workers.

- In India too, a dramatic reorientation would get support only once numbers are honestly laid out.

- The second argument for recording the data is so that all policies can be honestly evaluated on the basis of whether they meet the needs of the majority.

- Is a policy such as bank write-offs of loans amounting to ₹1.53-lakh crore last year, which helped corporates overwhelmingly, beneficial to the vast majority? Or has it been just beneficial to a thin sliver of the super rich?

- This would be possible to transparently evaluate only when the numbers of the poor are known and established.

- Third, if government data were to honestly account for the exact numbers of the poor, it may be more realistic to expect the public debate to be conducted on the concerns of the real majority and create a climate that demands accountability from public representatives.

- Fourth, India has clocked a massive rise in the market capitalisation and the fortunes of the richest Indian corporates, whose wealth has grown manifold in the past few years, even as millions of Indians have experienced a massive tumble into poverty.

- The stories of billionaires get reported regularly and prominently. To say that the stock market and the Indian economy are ‘not related’ is ingenuous.

- Indians must have the right to question whether there is a connection and if the massive rise in riches is not coincidental, but at the back of the misery of millions of the poor, whose ranks are swelling.

- If billionaire lists are evaluated in detail and reported upon, the country cannot shy away from counting its poor.

Importance of Poverty Estimation:

- Poverty estimates are not just important for academic purposes but are also crucial to track the impact and success of various government policies, especially social welfare schemes that are intended to eliminate poverty.

- BPL Census is conducted by the Ministry of Rural Development (along with the partnership of state), in order to identify the poor households.

- The Poverty estimates in the form of poverty line are used to formulate poor centric poverty elimination plans.

- Poverty estimation paves the way for poverty elimination, that in turn prepares the ground for a just and equitable society.

Conclusion:

The pursuit of becoming ‘Vishwaguru’, has hampered this as that pitch works only if the leadership is able to mask the dramatic rise in poverty.

The massive slide into poverty in India that is clear in domestic and international surveys and anecdotal evidence must meet with an institutional response.

The Government must girdle up and unflinchingly quantify the slide from the ‘fastest growing economy’ to the country with the largest rise in the number of poor people.

It must be accepted, to go back to the debate that it is “abject poverty” we are talking about; almost a sub-human level of existence of the majority of fellow Indians we cannot continue to be blase about.

Counting them would be a much-needed start to convey that each life matters.

[ad_2]